The Last Man Lost In WWI

To be the last person lost before the end of a conflict such as WWI is a bitter fate. The end of WWI was scheduled for a specific time and, with few exceptions, when the clock struck 11 am on November 11, 1918, all fighting ceased. In those last few minutes, however, there was some furious last-minute action and the last unfortunate soul to lose their life just one minute before 11 am was Henry Nicholas John Gunther.

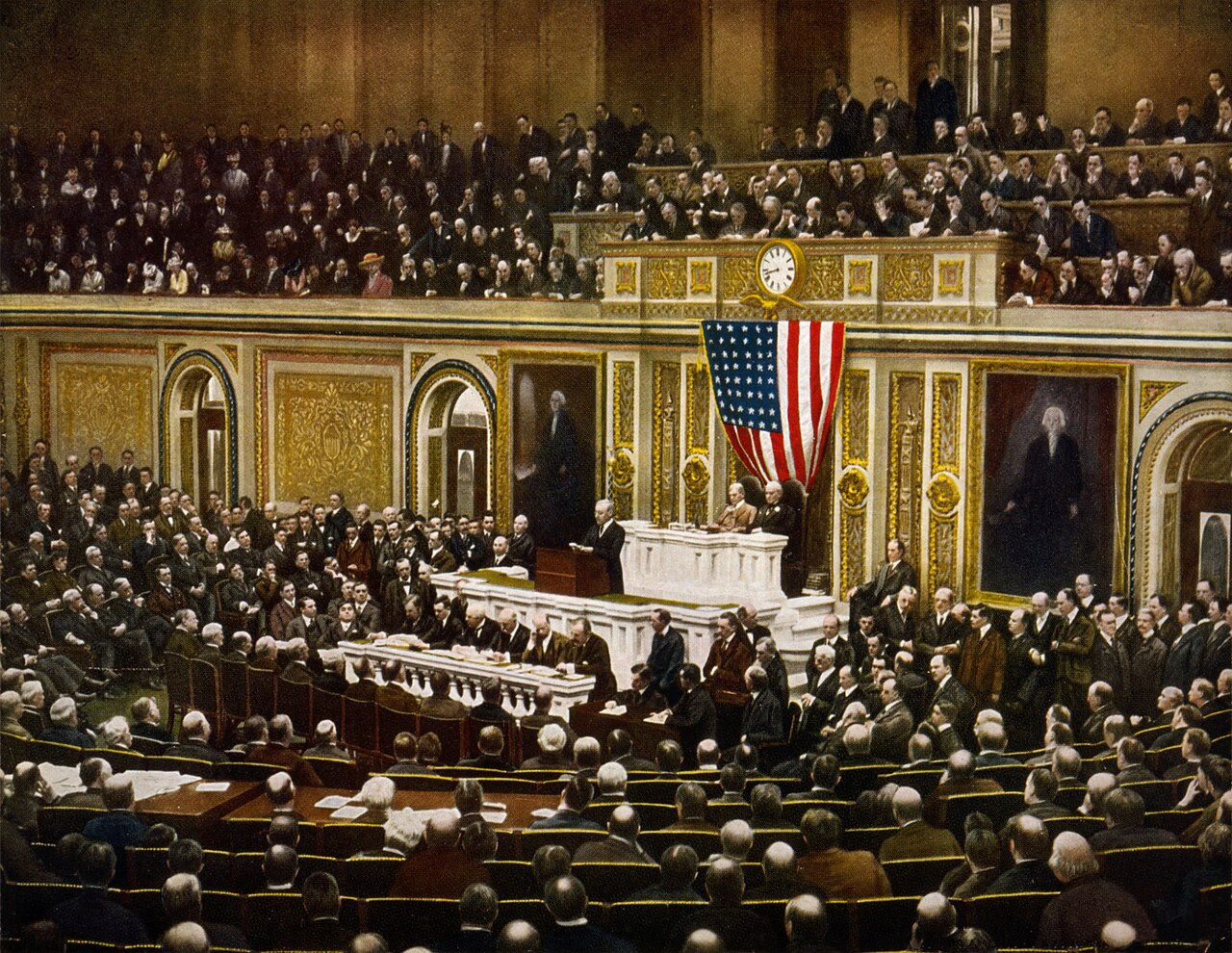

The End Of WWI

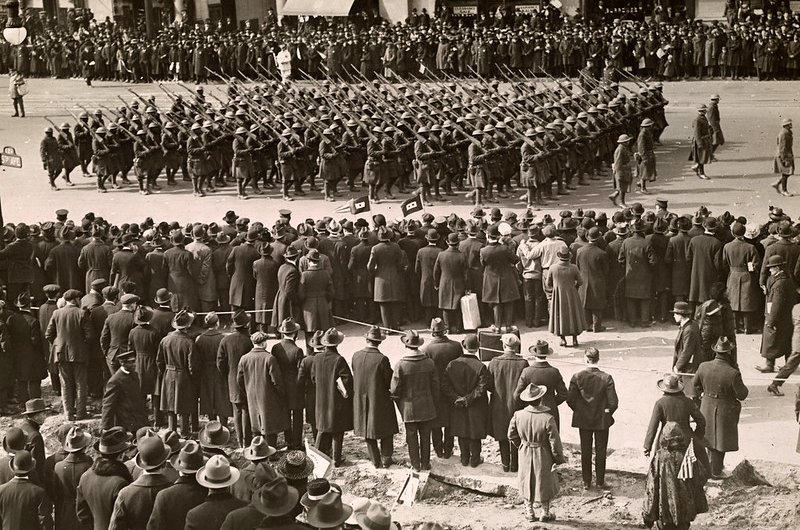

On the last day of WWI, the ceasefire came into effect at 11 am and until then, the fighting continued. It’s been estimated that in the time between the signing of the Armistice at 5 am, and the ceasefire six hours later, there were 11,000 casualties, far more than the average day during the previous four years.

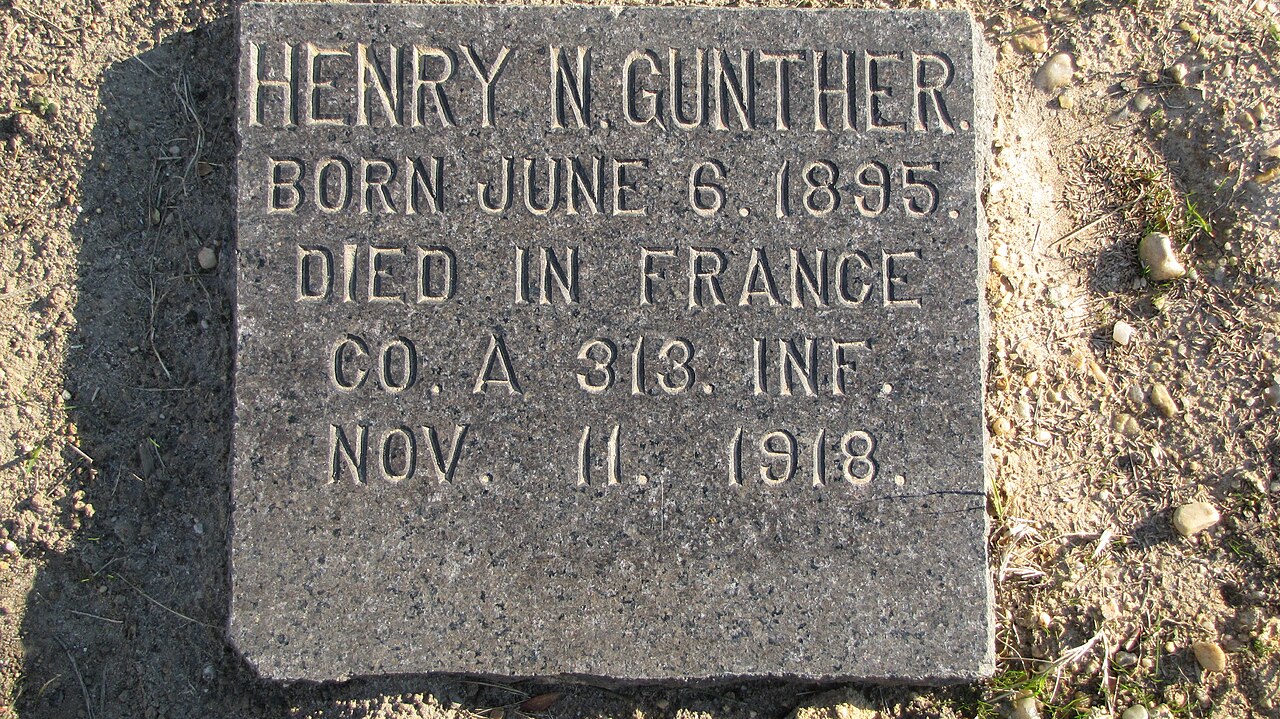

Concord, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Concord, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The End Of WWI

That was a larger casualty count than on the first day of the Normandy landings, 27 years later during WWII. Hundreds lost their lives, thrown into battle by generals who knew that the Armistice had been signed and that WWI was effectively over.

The End Of WWI

The American general William M Wright, knowing the Armistice had been signed, nevertheless ordered his men into battle. By 11 am, there had been more than 300 casualties, including 61 who lost their lives.

Harris & Ewing, Wikimedia Commons

Harris & Ewing, Wikimedia Commons

The End Of WWI

Wright didn’t want the Germans to occupy the French town of Stenay after the Armistice took effect. The town was known to have many bathhouses and Wright wanted to take advantage of that, to clean up his troops.

Rauenstein, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Rauenstein, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The End Of WWI

Henry Gunther is the last known person to lose their life just before the 11 am ceasefire. Each nation has a recognized “last” and there are some identified persons who were the first to be lost. Even before the fighting officially began, there were casualties.

The End Of WWI

A British citizen, Henry Hadley, is sometimes described as the "first British casualty" of WWI. Hadley was in Germany when WWI began. The day before Britain officially started fighting, German authorities attempted to arrest Hadley as an enemy alien, but he was shot while attempting to flee.

The End Of WWI

The first serviceman of the German Empire to lose his life is also the accepted first casualty of WWI. Albert Mayer lost his life in a brief skirmish between the French and Germans, technically a day before fighting officially began.

Imperial German Army, Wikimedia Commons

Imperial German Army, Wikimedia Commons

The End Of WWI

Jules-André Peugeot was the first French casualty. This happened in the same clash as that which took Albert Mayer’s life. Peugeot was lost a few moments after Mayer.

National Library of Scotland, Picryl

National Library of Scotland, Picryl

The End Of WWI

Augustin-Joseph Victorin Trébuchon was the last French serviceman lost in WWI, 15 minutes before the ceasefire. French officials were embarrassed to have sent men into battle after the Armistice had been signed and recorded Trébuchon as being lost the day before. It was only later corrected.

Collection Vrigne-Meuse, Wikimedia Commons

Collection Vrigne-Meuse, Wikimedia Commons

The End Of WWI

Belgium had been neutral at the outbreak of WWI when Germany invaded the country as a means to enter France. Marcel Toussaint Terfve was a Belgian corporal in WWI. He is known as the last Belgian to be lost, at 10:45 am, 15 minutes before the ceasefire.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

The End Of WWI

Three Americans share the distinction of being the first to be lost after their country’s entry into WWI. On November 3, 1917, Private Thomas Francis Enright, Private Merle David Hay, and Corporal James Bethel Gresham all lost their lives in the first American fighting, although it’s impossible to know exactly when each of them was lost.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

The Early Life Of Henry Gunther

Baltimore had a thriving German American community prior to WWI. Germans were the largest foreign-born ethnic group in Baltimore. By 1914, the German population was 94,000, 20% of the population of Baltimore.

Concord, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Concord, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Early Life Of Henry Gunther

Many of the city’s schools were known as German-English, offering classes in both languages and by the end of WWI, one-third of the schools still offered German-language curricula, with a quarter of the people of Baltimore able to speak fluent German. Henry Gunther was born in 1895 into a German family in east Baltimore.

The Early Life Of Henry Gunther

Gunther’s parents, George Gunther and Lina Roth, were themselves children of immigrants. He grew up in Highlandtown, a neighborhood with a German majority, and the family were devout Catholics. Prior to being drafted in 1917, Gunther worked as a bookkeeper and clerk at a bank.

Anti-German Sentiment

Henry Gunther did not immediately enlist in the armed forces upon the US entry into WWI in April 1917. The United States had conscription but it was seen as a matter of honor in that time period to serve.

Anti-German Sentiment

Prior to the US involvement, many Americans lobbied the government to stay out of the conflict. Many of those voices against American involvement came from German-born Americans. Before the US entry into WWI, many German Americans openly supported Germany against Britain, France, and Russia.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Anti-German Sentiment

Although many other groups opposed US involvement, it was often seen as disloyal to the United States to support Germany. Fear of immigrants is something that arises during times of crisis.

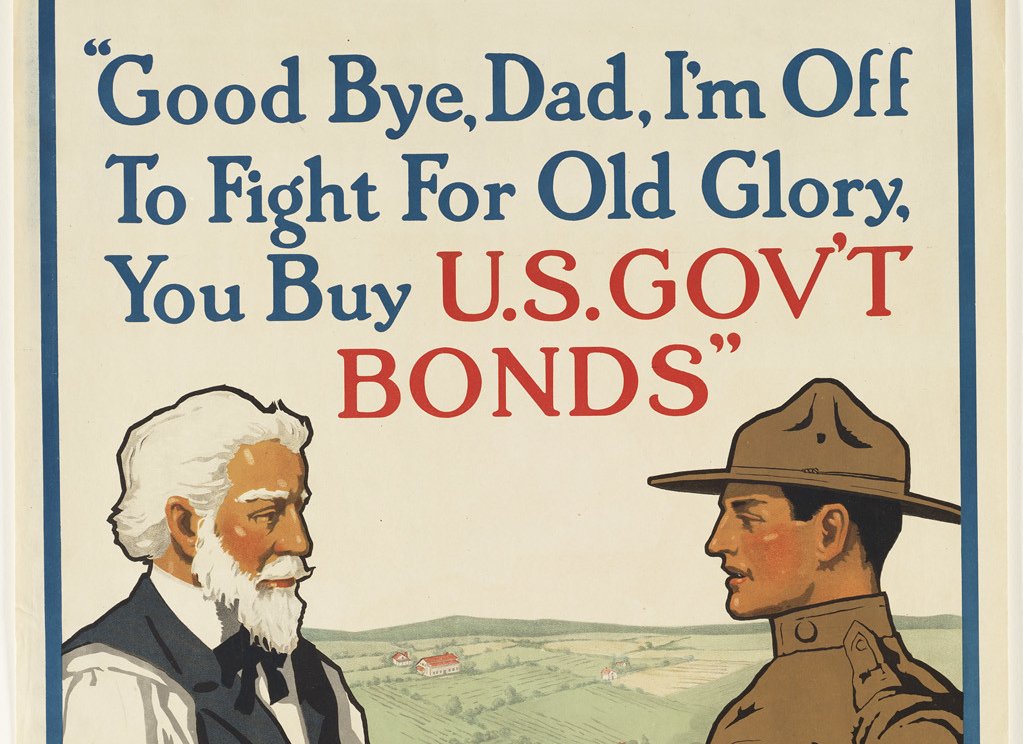

National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

Anti-German Sentiment

With the conflict raging overseas and the fear that the United States would become involved, immigrants became a convenient scapegoat. When the US entered WWI in 1917, the fear was that German Americans would support Germany.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Anti-German Sentiment

Many areas in the United States issued decrees requiring English-only in public. These laws affected not only Germans, but also other ethnicities easily mistaken for German, such as Dutch, Scandinavians, and people who spoke German from areas outside the German Empire or the Austro-Hungarian Empire, such as Switzerland.

Downtowngal, Wikimedia Commons

Downtowngal, Wikimedia Commons

Anti-German Sentiment

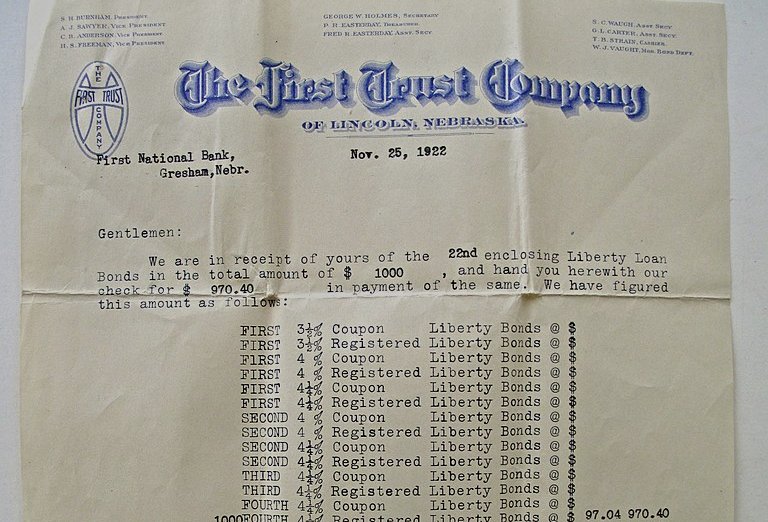

Church services in many languages were now illegal. Schools stopped teaching German, even in German-as-a-second language courses. German Americans were also required to buy Liberty Bonds, which were put in place to support the US forces.

Anti-German Sentiment

Patriotic celebrations became mandatory and anyone not taking part would be looked at with suspicion. There were book burnings of German language books and families stopped celebrating German traditions.

Walter Rease Allman, Wikimedia Commons

Walter Rease Allman, Wikimedia Commons

Anti-German Sentiment

There was violence and even a few cases of lives lost in the climate of fear. German names were changed to more Anglo-American-sounding names. It was within this tense situation that Henry Gunther found himself.

Antony-22, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Antony-22, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Army Service

There is no evidence that Gunther’s reluctance to volunteer had anything to do with sympathies for the German Empire. With both parents born in the US, Gunther’s connections to Germany were minimal.

Don...The UpNorth Memories Guy, Flickr

Don...The UpNorth Memories Guy, Flickr

Army Service

However, the growing anti-German sentiment would have played a role in joining, even if it put to rest any questions of loyalty on Gunther’s part. In September 1917, Gunther was drafted and assigned to the 313th Infantry Regiment, also known as "Baltimore's Own”.

Army Service

This was part of the larger 157th Brigade of the 79th Infantry Division. Gunther’s clerical experience served him well and he was quickly promoted to supply sergeant, in charge of clothing for his unit.

Army Service

Gunther arrived in France in July 1918 as part of the American Expeditionary Forces. Experiencing the hardships of life in the trenches first-hand, Gunther wrote a letter to a friend back home, urging him to try anything to avoid being drafted and sent to those “miserable conditions”.

Nationaal Archief, Wikimedia Commons

Nationaal Archief, Wikimedia Commons

Army Service

This letter was intercepted by the army postal censor. Speaking ill of life in the army or being critical of the army in any way, especially by mail, was a serious offense. Not only was he advising someone to “avoid being drafted” by any means, Gunther was also disparaging army life, seen as potentially harming morale.

National Library of Scotland, Picryl

National Library of Scotland, Picryl

Army Service

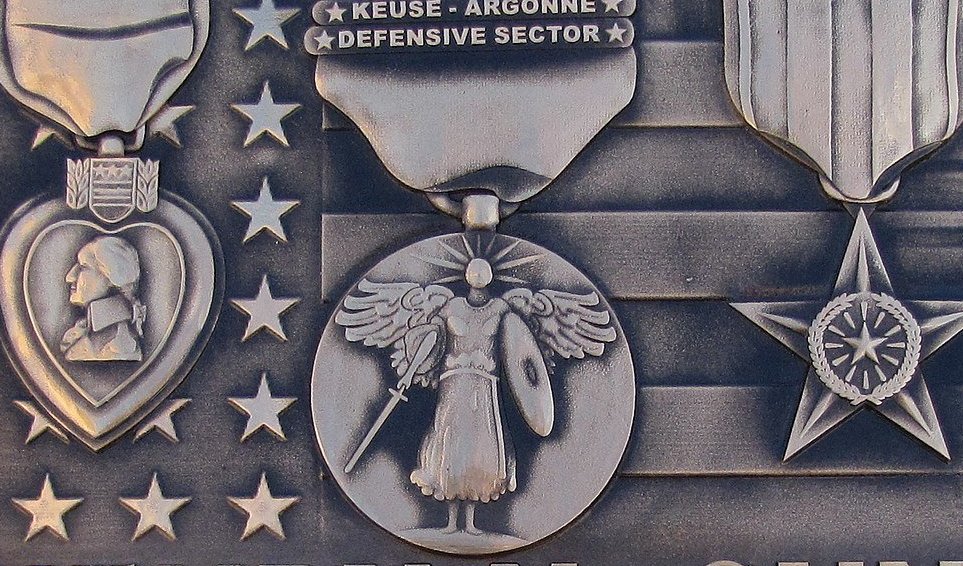

Gunther was demoted from sergeant to private. His unit, Company A, arrived at the Western Front on September 12, 1918. This unit was part of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and was still involved in fierce fighting until November 11.

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Picryl

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Picryl

Army Service

As the Armistice was being signed at 5 am, Gunther’s squad approached a roadblock. A small group of Germans were preventing access to the village of Chaumont-devant-Damvillers near Meuse, in Lorraine.

WCOMFR, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

WCOMFR, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Army Service

Against the orders of his friend and commander, Sergeant Ernest Powell, Gunther charged the position of the Germans with a fixed bayonet. The Germans were aware that the ceasefire was only minutes away and they tried to wave him off.

Army Service

Gunther kept running and fired a number of shots. When he got too close to the Germans, they opened fire and Gunther was gone.

Army Service

A reporter for the daily newspaper The Sun interviewed Gunther’s comrades afterward. They told him that Gunther had “brooded a great deal over his recent reduction in rank” and was determined to “make good” before his comrades.

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Picryl

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Picryl

Memorials

The commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, General John J Pershing, issued an “Order of The Day” on November 12, specifically mentioning Gunther as the last American lost in WWI. The US Army posthumously restored his rank of sergeant and posthumously awarded him a divisional citation for gallantry in action and the Distinguished Service Cross.

Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Memorials

A veterans’ organization named a chapter in east Baltimore after Henry Gunther, several years after the end of WWI. That chapter closed in 2004.

Concord, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Concord, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Memorials

Gunther’s remains were returned to the United States in 1923. He had been exhumed from a cemetery in France and buried at the Most Holy Redeemer Cemetery in Baltimore.

Concord, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Concord, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Memorials

There was an investigation launched after WWI. It was revealed that during Armistice negotiations, the French commander-in-chief, Marshal Foch, refused to accept the German negotiators' request to declare an immediate ceasefire or truce in order to prevent more human loss.

Nationaal Archief, Wikimedia Commons

Nationaal Archief, Wikimedia Commons

Memorials

This failure to declare a truce immediately after the signing of the Armistice and instead waiting for “the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month” is considered a travesty and a completely unnecessary waste of life. During those six hours between the signing of the Armistice and the 11 am ceasefire, 11,000 additional men were wounded or lost their lives.

Université de Caen Basse-Normandie, Picryl

Université de Caen Basse-Normandie, Picryl

Memorials

On November 11, 2008, a memorial was constructed at Chaumont-devant-Damvillers in Lorraine, near where Gunther lost his life. Two years later, on November 11, 2010, a memorial plaque was unveiled by the German Society of Maryland at his gravesite at 10:59 am.

Concord, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Concord, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Memorials

On that same day, at Henry Gunther’s grave at the Most Holy Redeemer Cemetery in Baltimore, another commemorative plaque was unveiled. In October 2017, the centenary year of the United States' entry into WWI, and 99 years after Gunther’s loss, a new US flag was hoisted at Chaumont-devant-Damvillers in Lorraine in dedication to Henry Gunther.