Blank Slate

Just East of the Phoenix gate in the Qianling Mausoleum in China, an enormous tablet rises from the ground. Despite its size, it’s wordless; un-inscribed except for a few carved dragons and plump oysters at its peak. Though the monolith stands like a mute sentry, what lies beneath it has more than a few stories to tell.

The Qianling Mausoleum, you see, is the final resting place of the Emperors of the Tang Dynasty—and the one true Empress of China, the ruthless Wu Zetian. Empress Wu infamously rose to great power from humble beginnings, and she certainly didn’t do it by being shy, polite, or non-homicidal. In fact, Wu laid to rest many of the men and women who are now buried beside her.

Yet for all her dark exploits, the blank tablet above Wu and her victims also points to a lapse in her history. The Empress’s official record is teeming with information, but lacks any certainty. She was vilified by her (numerous) enemies, over-praised by her lackeys, and her attempt at founding a dynasty dissipated as quickly as her memory.

But these slippery fantasies are understandable—from a sexy mad monk lover to alleged infanticide, Wu’s life was the stuff of fairytales and nightmares.

A Total Eclipse of the Heart

Wu’s rise to power is wrapped in mystery and legend, and her birth is no different. The year she was born, 624, was ominously said to be the same year as a total solar eclipse.

Her family was well-connected, and once even put up a future Emperor of the Tang Dynasty, Li Yuan, in their home. When Li rose to power, he made sure to thank his gracious hosts with ample favors and riches.

Growing up in this luxury, Wu didn’t have much in the way to do with household chores, and her doting father allowed his daughter to study and read during her free time, making her one of the more educated women of her day. It paid off:

at 14, Wu became an Imperial concubine to Li Yuan’s son, Emperor Taizong. Wu’s mother reportedly wept as her daughter was leaving for the palace, but Wu only turned back and replied, "How do you know that it is not my fortune to meet the Son of Heaven"?

Wikimedia Commons Tang Emperor Taizong gives an audience to Gar Tongtsen Yulsung, the ambassador of Tibet.

Wikimedia Commons Tang Emperor Taizong gives an audience to Gar Tongtsen Yulsung, the ambassador of Tibet.

Despite her lofty ambitions, the newly minted concubine Wu didn’t exactly light up the inner chambers of the palace. Historians believe that she and the Emperor had intimate relations at least once, but she was far from Taizong’s favorite bedmate. She did, however, catch the eye of Taizong’s youngest son Li Zhi, the future emperor, and likely started an affair with him while the Emperor was still alive. Remember everybody:

sharing is caring.

Dirty Deeds

When Taizong died in 649, etiquette demanded that Wu cart herself off to a remote Buddhist convent for the rest of her life. As you’ve probably guessed, Wu was having absolutely none of that. Some records state she posted up in the convent for the briefest of periods before worming her way back into the good graces of the Li Zhi, by then the new Emperor Gaozong.

Other accounts, however, claim she never even left the Imperial Palace and just stubbornly stuck around, making her “services” available. Either way, it worked out. By 650, she had escaped the dreary promises of convent life and was one of Gaozong’s high-ranking concubines.

There were still exactly two problems in her way:

Gaozong already had an official consort, Empress Wang, and a favorite concubine, Consort Xiao. But this was child’s play for Wu, and pretty soon she had Gaozong eating out of the palm of her hand while both Wang and Xiao were sidelined. Of course, Wang still was Empress, and Wu couldn’t have that. So what did she do?

Well, this is where things get really interesting.

According to the darkest accounts, Wu strangled or otherwise killed her newborn baby daughter. She proceeded to blame the death on Empress Wang, who was arrested, deposed in favor of Wu, and later killed—along with Consort Xiao, for good measure. Suddenly, she was Empress Wu, official consort.

Whether or not Wu actually killed her own child in a Faustian bid for power is up for debate: some scholars suggest the culprit was crib death or accidental asphyxiation, a senseless tragedy that Wu just mercenarily used to her own advantage. So, much better, right?

Reign Over Me

The next stages of Wu’s rise were rapid and monumental. Gaozong was a sickly man, and soon Wu was managing the country pretty much without him.

Perhaps surprisingly, the people loved her. She was incredibly efficient, ridding China’s bureaucracy of corrupt ministers, and even her enemies had to admit she had a rare talent for the job. And she had a lot of enemies: Wu also showed a talent for bloodsport, and in these years she accused, exploited, or executed an impressive collection of adversarial counsellors, court figures, and royal relatives who stood in her way.

But she was just getting started.

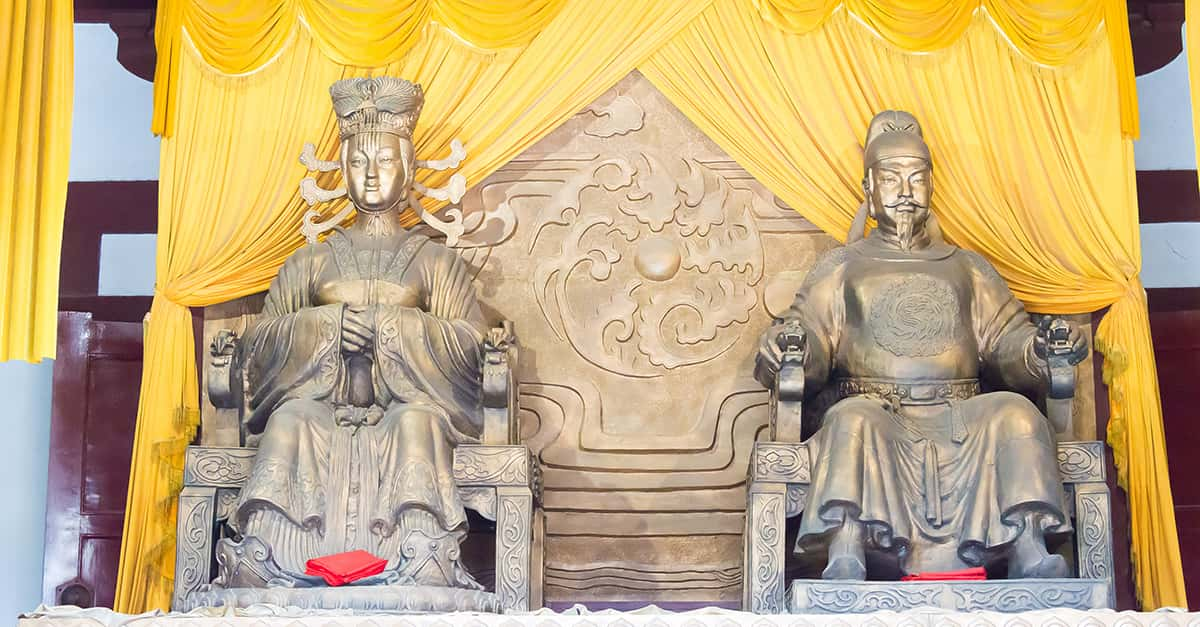

Shutterstock Statues of Wu Zetian and Emperor Gaozong at Huangze Temple.

Shutterstock Statues of Wu Zetian and Emperor Gaozong at Huangze Temple.

Emperor Gaozong died in 683, and Wu became Empress regent for her young son Zhongzong—that is, she was basically the de facto ruler of China. Then, when Zhongzong didn’t show proper deference to mommy dearest, Wu booted him out after just six weeks and replaced him with his younger, more pliable brother, the Emperor Ruizong.

At this point, Wu just let it all hang out.

She no longer hid behind a screen while giving advice, so everyone could now hear and see her relaying commands to the young boy-puppet. When courtiers tried to remove her from power in 684, she simply massacred 12 houses of the Imperial family, as one does. In 690, Wu finally made Ruizong give up the throne entirely, establishing her own shiny new Zhou dynasty.

Poor Ruizong was never even allowed to move into the Imperial quarters. Dang, son. With this, Wu settled into power.

Zhou Bisou Bisou

The later years of Wu’s power read like textbook Disney villainy, at least from the perspective of the sources we have left. First, Wu (probably) had an affair with a bonkers Buddhist monk named Huaiyi, who I like to think of as the Imperial Chinese version of Rasputin.

Huaiyi liked busting into the palace courtyard on horseback and demanding that 10 eunuchs attend to him. The eunuchs were very reluctant to do this, though, because Huaiyi also loved to beat on anyone and everyone who came near him. Sounds like someone had some intimacy issues.

But Wu also had a secret police force that was even worse than mad monk Huaiyi, if you can imagine.

They had all your garden-variety secret policing covered—violent interrogations, false accusations, political machinations, yada-yada—but they really excelled at surveillance. Remember, Wu was a great administrator, and one of her innovations was to install copper mailboxes around government offices. While you might think these were feedback boxes for the Empire, they were actually designed so that people would tattle on each other to the secret police.

I don’t want to make any generalizations, but we women do know how to gossip.

One last detail from Wu’s final years: well into old age, she took up two new lovers, the Zhang Brothers. The brothers were said to be perfectly manicured, elegant, and very into makeup, so whether they romped with Wu in the bedroom or they just all watched Sex and the City reruns together remains unknown—and then again, why not both? Either way, the Zhangs were certainly fun to have around, and as Wu grew older and weaker, they were often the only people she trusted to visit her—which made their violent deaths all the more tragic.

That’s right. In 705, aware of Wu’s weak state and her penchant for her two lovers, rebel leaders took their shot and mercilessly executed the Zhang brothers. On pain of death, they then demanded Wu restore the Tang Dynasty and give up her position to her elder son, the erstwhile Emperor Zhongzong.

Wu complied and escaped with her life, but it didn’t last long: she died before the year was out, and the Zhou Dynasty died with her. Sic transit glorious, feisty women.

Wikimedia Commons Epitaph for Yang Shun, general to Empress Wu Zetian.

Wikimedia Commons Epitaph for Yang Shun, general to Empress Wu Zetian.

The End of an Empire

These days, historians still debate whether to call the Zhou an actual dynasty. Ephemeral, unstable, and—gasp—female, Wu’s dynasty is seen as more of a curio, an interruption or even an aberration of the established Tang dynasty. Likewise, many of the records of her life are cautionary, sensationalized tales about what happens when you put a woman in power (answer:

an organized, efficient bureaucracy and fabulous best friends).

In short, we don’t have measured histories of the human woman Wu certainly was—what we do have is blatant propaganda, court rumors, and ancient whispers. Perhaps this is why her grave is unmarked; there is nothing to pin down.

Even so, we should continue telling her story in defiance of this gap—because the mark she left on China is indelible.