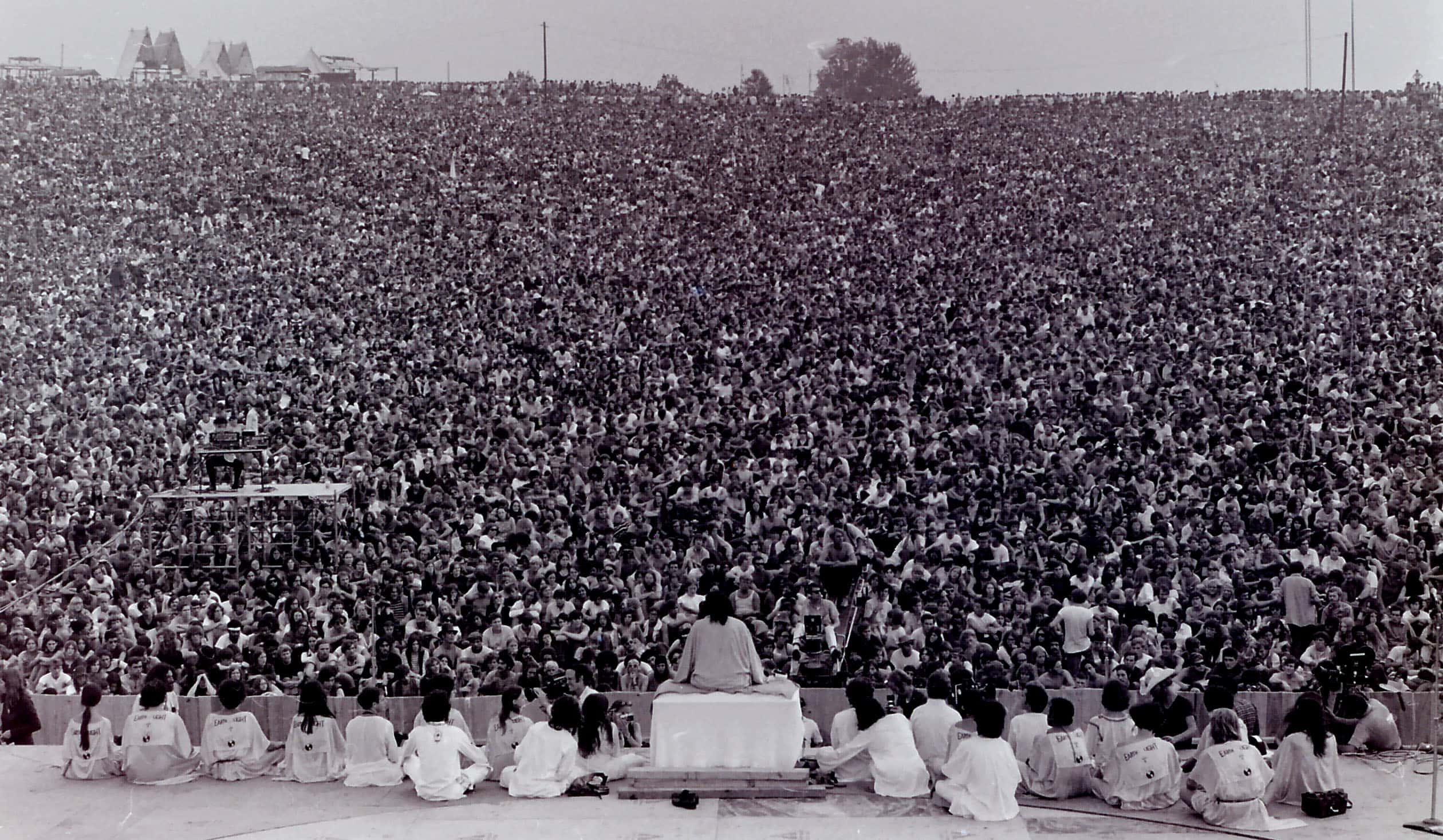

The violent story of Altamont has to start at the peaceful Woodstock, on the other side of the continent. Woodstock was one of the defining moments of the 1960s. Of hippies, and peace, and love, and idealism, and all that. Joni Mitchell called it “a spark of beauty”. A chance for hundreds of thousands of young people to feel like they were a part of something special—a real movement. It should have been a disaster. It shouldn’t have worked. But it did.

When the day came, the hundreds of thousands of people who bought tickets (and another couple hundred thousand who didn’t) showed up for the festival, turning a quiet town in New York’s Catskill mountains into a frantic hub of mud, traffic, and man-made electricity. Woodstock, and everything around it, was full to the brim. The festival’s organizers had meticulously planned the day, but they had vastly underestimated how many people would actually come. Things were beginning to grow tense.

3 Days of Peace and Music

The town of Bethel did not enforce its codes that day, for fear that it would only make the chaos worse. The governor of New York called one of the festival’s organizers, John Roberts, and threatened to send 10,000 troops from the National Guard to bring things under control. Roberts only barely managed to convince him otherwise.

Woodstock was a powder keg, and everyone seemed convinced it was going to blow at any minute.

It never did. While it didn’t go off entirely without a hitch, and there were sadly two deaths (one young man died from what is believed to have been an overdose, while another was run over by a tractor), Woodstock ended up being a remarkable testament to the peace and love movement on which it was based.

Max Yasgur, the dairy farmer who owned the land on which Woodstock was held, was moved by the festival.

He noted, very accurately, that it could have devolved into an utter catastrophe of rioting and violence. But instead, all these people lived up to the spirit of the day and spent the festival coming together and enjoying the music that they all loved. Yasgur spoke of the idealism that he felt after he’d volunteered his land for this historic day: "If we join them, we can turn those adversities that are the problems of America today into a hope for a brighter and more peaceful future..".

Woodstock closed with Jimi Hendrix.

The legendary guitar player, clad in a red headband and a fringed blue and white shirt, took the stage at 9am on Monday, August 18, 1969, capping off a day of music that had started at 2pm and run, literally, all night. Deep into his set, he played his iconic version of the Star Spangled Banner, ending three (and a half) days of music with one of the most enduring and iconic images of the 1960s.

Against all odds, Woodstock ended up being one of the most remarkable moments of the entire decade—seemingly proof that the bright-eyed hope of its young counterculture was not misplaced.

Woodstock West

Woodstock had so many of the greatest bands of the 1960s—The Grateful Dead, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Janis Joplin, The Who, Jefferson Airplane, The Band—but maybe the biggest act in the world at the time, The Rolling Stones, were not present. Not long after, however, the Stones embarked on a North American tour, and with the memory of Woodstock still fresh in everyone’s minds, a plan for another such event began to take shape.

There are conflicting stories about the exact origins of Altamont.

According to members of Jefferson Airplane, they had planned to create a sort of “Woodstock West” featuring them, the Grateful Dead, and the Stones. Other sources say that the Stones themselves planned on putting on a free concert to appease public frustration with the ticket prices for their tour.

Regardless of how the idea formed, plans for a free concert in California got underway. Unsurprisingly, there were immediately several hitches, but with the confidence instilled by the “spark of beauty” in New York in August, organizers were sure things would all work out in the end. Spoiler:

they didn't.

The concert that would eventually be held at Altamont was never as well thought-out as Woodstock. Initially, the concert was meant take place in a practice field at San Jose State University, but San Jose wasn't exactly happy about having 100,000 youths around, so plans started forming around San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. What place could be better for Woodstock West than Frisco, a Mecca of the postwar counterculture?

Well, the park was hosting a football game that day and refused to issue permits for the concert. With the day fast approaching, plans moved to Sears Point Raceway in Sonoma. However, the owner of the raceway demanded too much money from the Stones, and once again, the concert needed to move.

That’s when a man named Dick Carter, who owned Altamont Speedway, came forward and offered it as an alternative. Organizers were out of time, so they accepted the offer out of desperation. Once the deal was in place, it became a mad scramble to get everything necessary—portable toilets, medical tents, not to mention the sound equipment and the stage itself—to Altamont.

It seemed impossible to get everything set up in time, but remarkably, the speedway was ready for a concert by December 6th, 1969.

It seemed like yet another testament to the 1960s counterculture and the ability to get together against all odds in the name of peace and love. However, before the show was over, the dream of recreating the magic of Woodstock would fall to pieces in a haze of beer, drugs, and violence.

Getty Images Mick Jagger performing at a later date.

Getty Images Mick Jagger performing at a later date.

Gimme Shelter

Rather than hire a traditional police force, the Rolling Stones decided that they’d bring in the local chapter of the Hells Angels to provide security (though the extent of the bikers' responsibilities as security is still disputed). Altamont was going to be the epicentre of a countercultural movement, they couldn’t have “the man” there as a sober reminder of the status quo. The bands, the audience, the Angels—they were all on the same side, weren’t they? What could go wrong?

Everyone was there to come together and enjoy some amazing music. Only months ago, this sort of optimism had allowed for Woodstock to happen, one of the defining moments of the ‘60s. So, with that blind confidence, the Stones’ manager bought the bikers $500-worth of beer and told them to keep people off the stage.

Sadly, the Rolling Stones’ belief in the Angels was misplaced. This was, after all, a violent and criminal gang they had hired, no matter how “countercultural” they all were. Though Altamont started smoothly, things began to sour as the day went on.

The crowd became agitated, which wasn’t helped by the increasingly drunk and violent Angels who were hanging out on the stage.

Let It Bleed

Things had gotten grim long before the Rolling Stones started their set. Denise Jewkes, the pregnant lead singer of a local band called the Ace of Cups, had been hit in the head by a beer can thrown from the crowd, fracturing her skull.

The Angels had armed themselves with broken pool cues and motorcycle chains as fights started to get more aggressive. Marty Balin, one of the singers from Jefferson Airplane, tried to break up a fight in the crowd, only to be knocked out cold by one of the Angels.

The Grateful Dead, sensing the disaster in the air, refused to go on stage, and simply left the venue for fear of their safety. This was the mood when the Rolling Stones stepped out onto the stage.

Woodstock was a powder keg that had every reason to go off, but didn’t. But at least Woodstock had the benefit of careful planning and weeks to prepare.

Altamont was a disaster almost from the start, and it was only a matter of time before the worst happened. And at the culmination of the event, while the Rolling Stones nervously tried to get through their set, the idealism that created Woodstock, that Max Yasgur believed made the future so bright, came into jarring contact with reality.

Meredith Hunter, an 18-year-old black teenager who had set out to Altamont, like so many, in the hopes of being a part of something special, was stabbed to death by Hells Angel Alan Passaro, just feet from the stage. Moments before, a drug-addled Hunter had attempted to get onto the stage, only to be savagely attacked by the Angels.

He returned soon after and drew a gun. Passaro charged at him, knocked the gun away, and stabbed him twice, killing him.

The Death of the 60s

Before the concert, Mick Jagger said, “It’s creating a microcosmic society which sets examples for the rest of America as to how one can behave at large gatherings”. (Though granted, in a more candid moment, he also said, “The concert is an excuse for everyone to talk to each other, get together, sleep with each other, hold each other, and get very stoned,” but essentially, the idea is the same). He hoped Altamont would prove that the American youth movement was ready to lead the world to a bright future, but instead it only proved how fragile that movement really was.

For a few magical months, the youth of America could look at Woodstock and truly believe that they were a part of something special and powerful. That they were, as Joni Mitchell said, “part of a greater organism”. But then, in the final weeks of 1969, Meredith Hunter was killed at a doomed attempt to recreate that magic.

The wild optimism that the miracle of Woodstock instilled led, in turn, to the tragic failure of Altamont.

Looking back, we all want to think of Woodstock as the defining moment of the 1960s, but sadly, the decade was never so simple. It was a dense and complicated time filled with hope and love, but also with violence and pain.

If you want to look at Woodstock as a microcosm of the decade, you can only do so by also looking at Altamont, the darker side of the same coin.

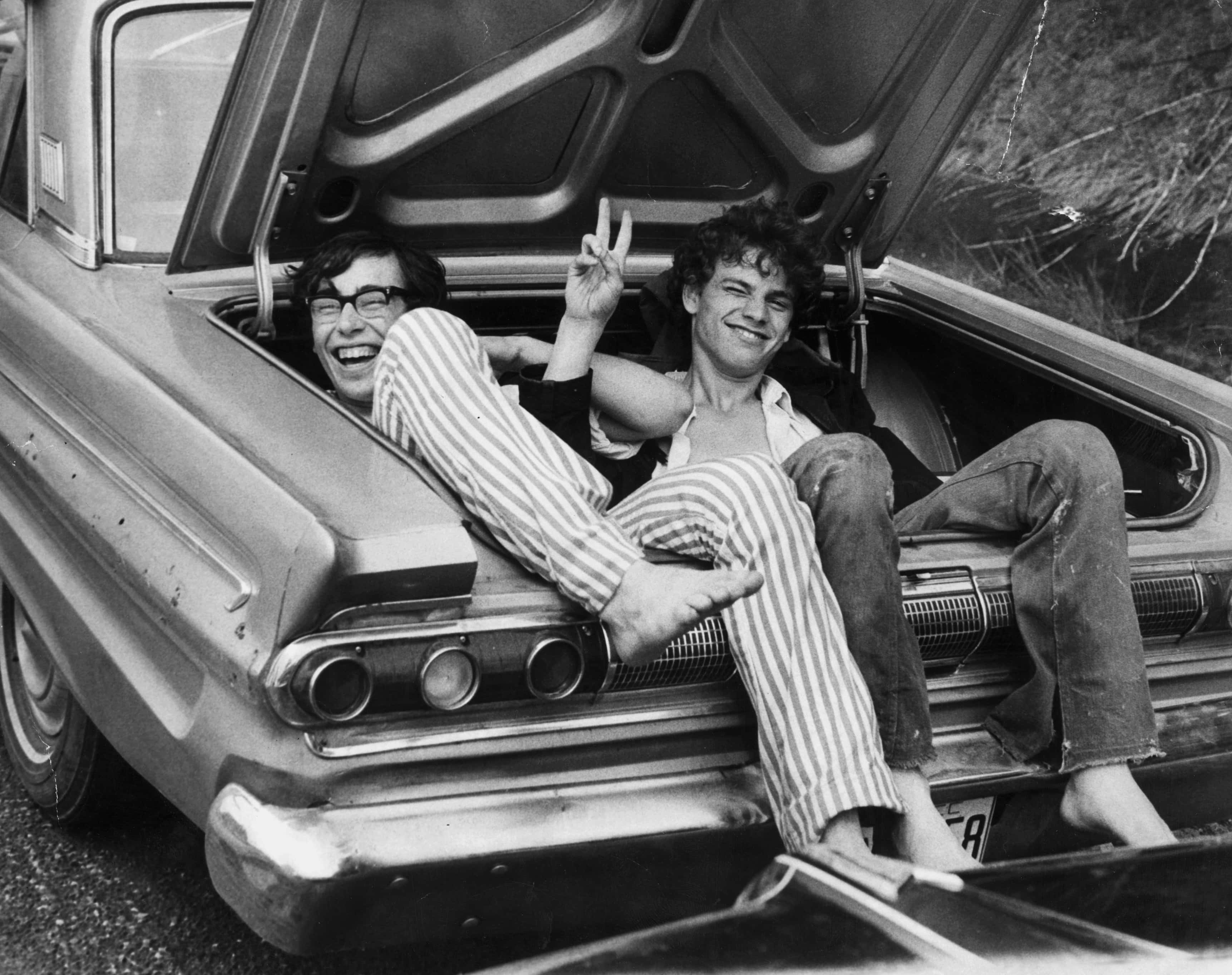

Getty Images Two Woodstock attendees.

Getty Images Two Woodstock attendees.