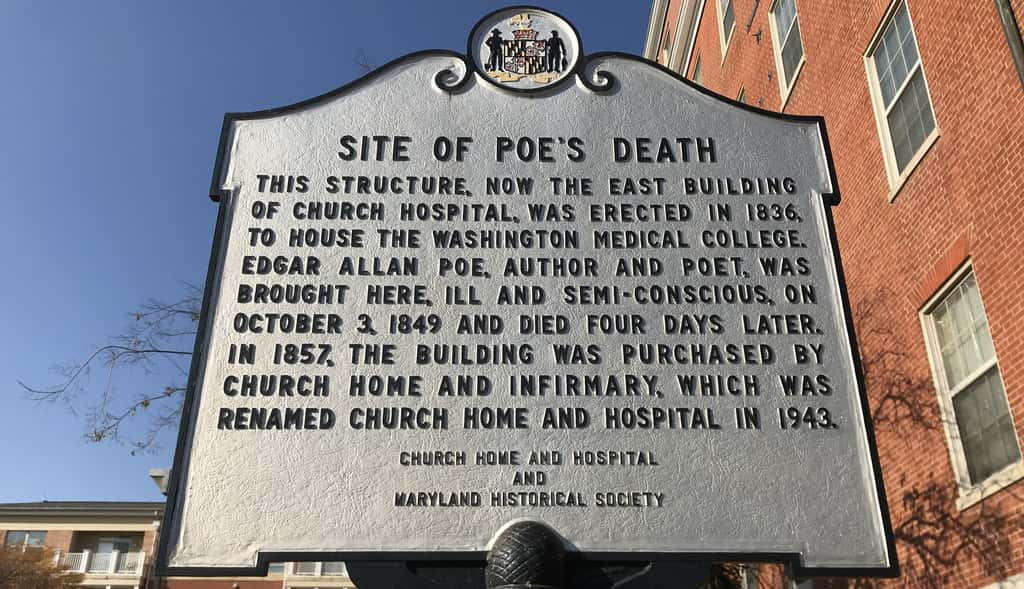

Edgar Allan Poe made his name writing strange, grotesque, and mysterious tales, so it is only fitting that he should have died a strange, grotesque, and mysterious death. On October 3, 1849, he was found completely incoherent in a Baltimore pub called Ryan’s Tavern. He was picked up by an acquaintance by the name of Dr. Joseph E. Snodgrass, who took him to a hospital, where he was cared for by Dr. John Joseph Moran.

By all accounts, the delirious Poe was found in a spectacularly monstrous state. He wore strange, ragged clothes that didn’t belong to him. His hair was a mess and his worn out face was unwashed. He could barely talk. Even stranger still, he kept calling out a single name, while in his atrocious state: “Reynolds.” Even today, we can only speculate as to what he meant—though clearly, it was something of desperate importance.

Only one thing was certain when Poe was found at Ryan’s: something had happened to this man. There were a thousand questions: What happened to him? Why was he dressed that way? Why was he even in Baltimore? The last he’d been seen, he was heading from his home in Virginia to New York City.

Sadly, he’d never be able to answer those questions—he died without ever returning to a lucid state. Allegedly, he said "Lord, help my poor soul” as he closed his eyes forever on October 7, 1849. Nearly everything we know about these strange, final days comes from Moran, but it’s generally agreed that the good doctor’s word is dubious at best, if not completely unreliable. So the mystery of what happened to Edgar Allan Poe has persisted, and it looks like the answers will never come.

Poe was buried in a cheap, unadorned wooden box, on a cold and rainy day, in a poorly attended ceremony. No one there, no one anywhere, knew what happened to put him there. But one jealous critic did know one thing: the strange and mysterious death of this dark and depressing genius was the perfect chance to make sure that his reputation ended up in the ground with him.

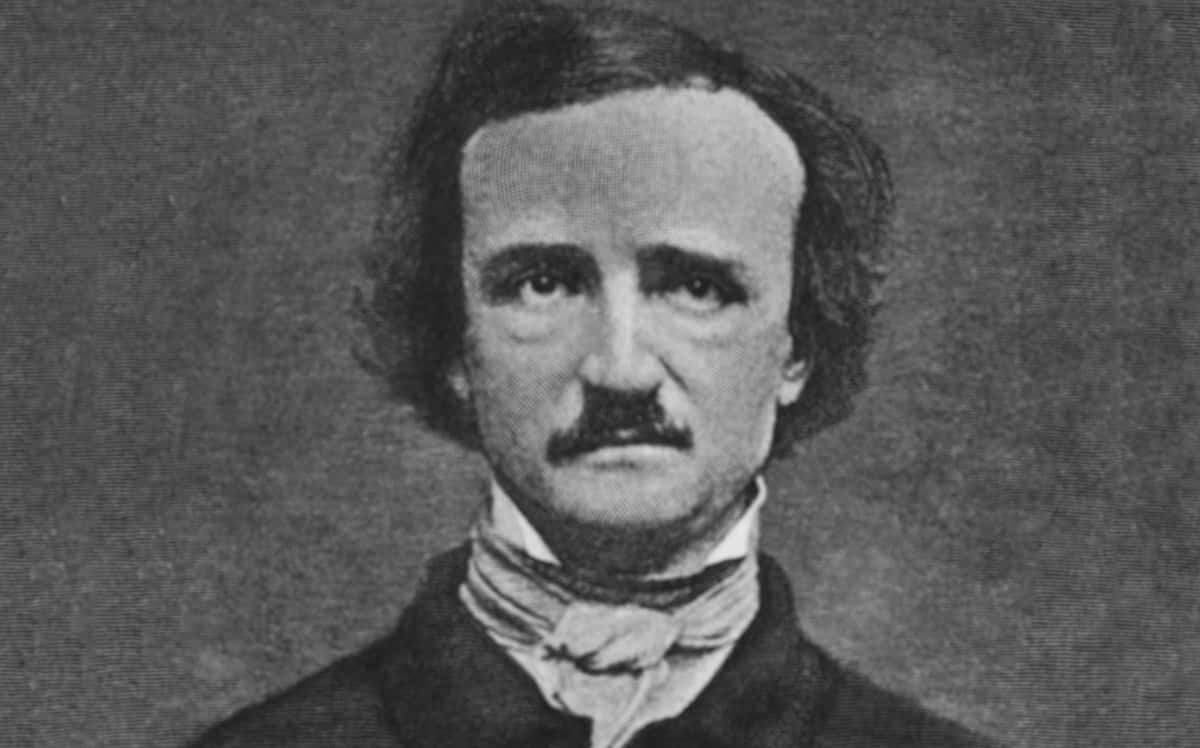

Wikimedia Commons The New York Tribune in 1864

Wikimedia Commons The New York Tribune in 1864

Two days after Poe died under such strange circumstances, his obituary was published in the New York Tribune, signed only with the name Ludwig. This was how it opened:

“Edgar Allan Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore the day before yesterday. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it.”

Not exactly high praise for a man who today is considered one of the greatest and most influential writers in American history. But what was more important than the writer’s obvious dislike of Poe was a bold claim: That Poe died as he lived—a delirious wreck.

“He was at times a dreamer, dwelling in ideal realms, in heaven or hell, peopled with creations and the accidents of his brain. He walked the streets, in madness or melancholy, with lips moving in indistinct curses, or with eyes upturned in passionate prayers for the happiness of those who at that moment were objects of his idolatry, but never for himself, for he felt, or professed to feel, that he was already damned.”

Readers of the Tribune read about the death of an insane man. The kind of man that you would expect to find ragged and incoherent shouting the name “Reynolds.” And for years, this was how people remembered Poe—as a masterful writer whose morbid work was only a small window into the utter madness within. This is far from the whole truth, but as it turns out, Edgar Allan Poe wasn’t exactly a popular figure in life, and his bizarre and mysterious death paved the way for a truly remarkable character assassination that convinced the world the price for his genius was sheer lunacy.

Poe came from a difficult childhood—his father left the family when he was barely a year old, and his mother died soon after. He was taken in by the Allan family, who fostered him but never adopted him. When the time came, he went to Thomas Jefferson’s newly established University of Virginia, which, under its system of “student self-government,” was utter chaos.

He became estranged from his foster father over money issues. Poe said that his father didn’t give him enough money to register for classes; his father said that Poe gambled away all of the money he’d received. The money stopped, and the debt issues that would follow Poe throughout his life began.

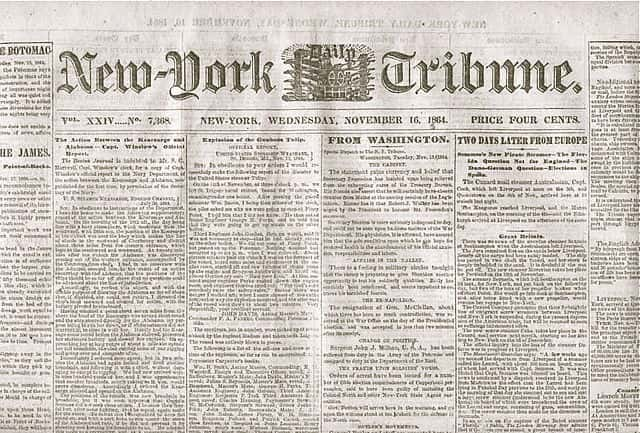

After some modest success in the literary business, Poe published what is still arguably his most famous work: The Raven. The poem was undeniable, and it almost immediately made Poe a household name—though, in a sad example of the fickle literary world of the 19th century, he was only paid $9 for writing it. Still, though, the fame that came with the iconic poem planted Poe firmly in literary society, and it didn’t take him long to start making enemies in that world.

Wikimedia Commons Illustration by Édouard Manet for a French translation by Stéphane Mallarmé of Edgar Allan Poe's "The Raven."

Wikimedia Commons Illustration by Édouard Manet for a French translation by Stéphane Mallarmé of Edgar Allan Poe's "The Raven."

Poe was undeniably popular in his life, but that didn’t mean he was particularly well-liked. Is it any surprise that the man who wrote The Telltale Heart and The Pit and the Pendulum wasn’t exactly a bundle of joy? Despite his talent, he proved to be abrasive and difficult, and he seemed to make a detractor for every admirer. So when Poe died, delirious and alone, surrounded by mystery, his greatest critic was quick to take the chance to make sure history remembered him as a depraved lunatic.

The anonymous “Ludwig” who wrote Poe’s scathing obituary was, in fact, a poet, editor, and critic named Rufus Wilmot Griswold. He may not be very well known today, something Poe would likely be delighted to hear, but the two men were quite well acquainted in life—and they hated each other’s guts. It started when Poe publicly denounced an anthology of poetry that Griswold published. Griswold didn’t take too kindly to the criticism, and from that point on the two seemed to butt heads at every turn—though to be fair, Poe butt heads with all kinds of people.

Poe and Griswold couldn’t seem to shake one another, competing over jobs and women all while publicly trading jabs. But when Poe died, Griswold saw an opportunity. His obituary—which, by the way, he stole from the novel The Claxton almost word for word, though nobody seemed to notice or care—hit the papers just two days after Poe’s death, and just like that, the destruction of a great writer’s legacy was underway.

Wikimedia Commons Engraving of Rufus Wilmot Griswold

Wikimedia Commons Engraving of Rufus Wilmot Griswold

Anyone who knew anything about the relationship between Griswold and Poe ought to have understood that the two of them hated each other, yet once the man died, Griswold somehow managed to convince the world that he was the authority on all things Poe. He claimed that Poe had made him his literary executor, and bafflingly, people took him at his word.

Not long after Poe’s obituary appeared in The Tribune, Griswold published something titled “Memoir of the Author” in a collection of Poe’s work. It was called a memoir, but it was largely fabricated by Griswold, and it painted Poe like a man who lived as he’d died—a drunk, drug-addicted lunatic. And people ate it up.

Likely because Poe’s works were so dark, people were completely willing to believe that the writer echoed the page. While there have been many efforts to repair Poe’s reputation, it was too late. Even today, people tend to remember Poe through Griswold’s lens. His campaign to destroy Poe’s reputation was, by all accounts, a resounding success. The bizarre circumstances of Poe’s final days had made it all too easy.

The death of Edgar Allan Poe remains a mystery. Why was he in such a haggard state? Why was he wearing someone else’s clothes? What was “Reynolds” supposed to mean? It’s a grim tale that’s eerily befitting the man himself. But one writer, at least, knew that it didn’t matter why he died. All that mattered was how. That was enough to make sure that the world would forever more remember Poe as a raving drunk and a madman.

Flickr Plaque at the site of Edgar Allen Poe's death

Flickr Plaque at the site of Edgar Allen Poe's death

But now, after centuries have passed, does it even matter? It’s true, far too many people remember Poe the way that Griswold falsely portrayed him. But, if anything, it only adds to the grotesque master’s mystique. The idea of the damned writer wandering the streets, muttering and cursing is undeniably alluring. And, to point out the obvious, though I’m sure that Griswold felt a petty satisfaction at the way he warped the world’s memory of his enemy—it was, after all, his greatest accomplishment—let’s remember that Poe wrote The Black Cat. The Pit and the Pendulum. The Raven. I still think he’s got the edge in the rivalry, mumbling madman or not.