The Emu War

In 1932, after a roving mob of migrating emus destroyed valuable crops, Australia declared war on the flightless birds. The emus won—but there’s a lot more to the story than just its unlikely punchline.

Welcome Back

It all began following WWII, when some Australian veterans returning home from Europe were promised land to farm on in Western Australia. The government re-allotted crown land and other land they’d acquired for this purpose—but not all land was created equal, and some parts were more difficult to farm on, putting these veterans in a precarious position.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

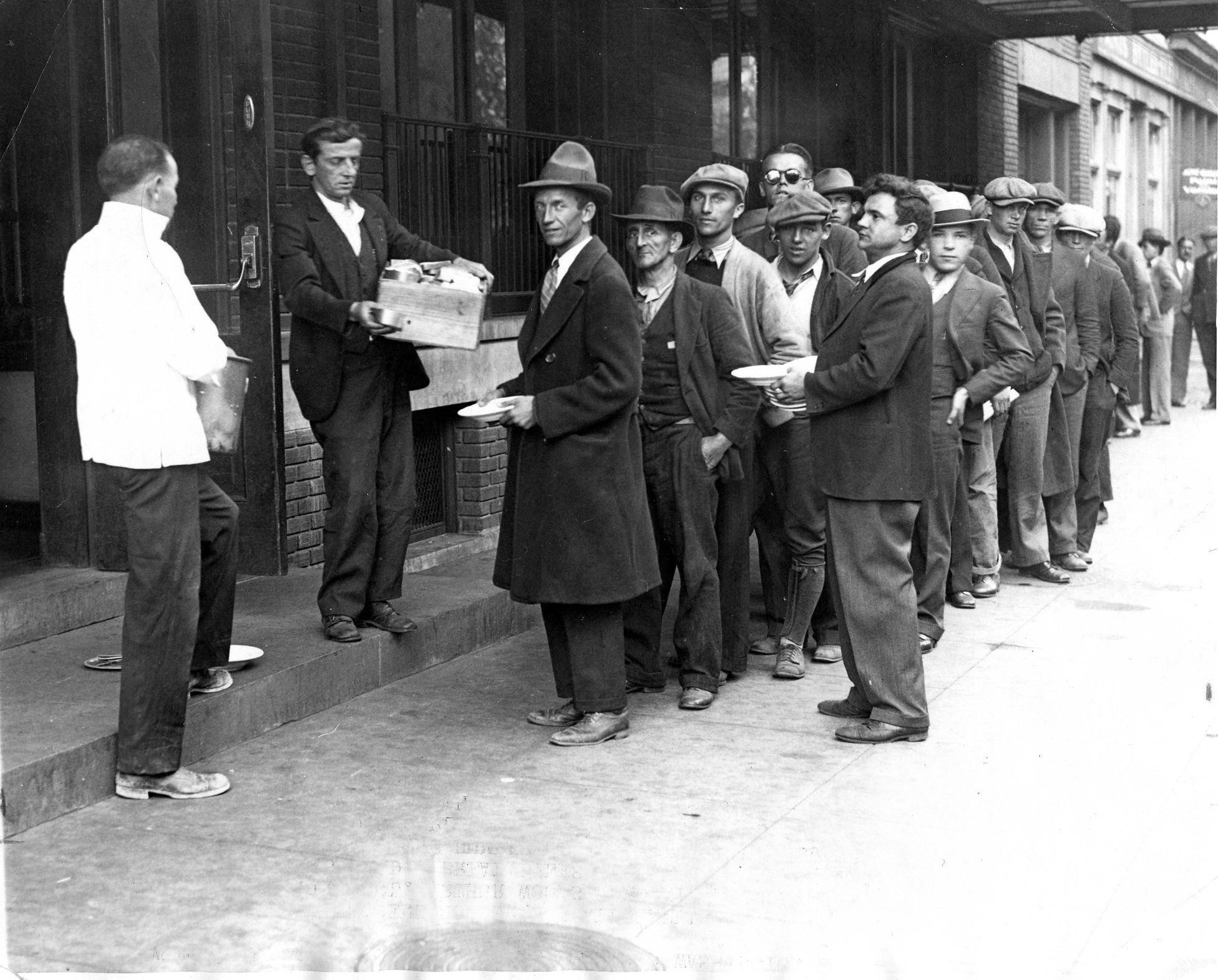

The Great Depression

This program continued through the 1920s—and then, disaster struck. With the Great Depression of 1929, the Australian government was under serious pressure to keep its economy afloat and keep its people fed. And they looked to the wheat farmers who’d received land after the war.

Economics 101

The government wanted the farmers to ramp up production, and promised subsidies. Not only did those subsidies never go through, they drove the price of wheat down. The farmers were furious—and it all came to a head in 1932.

The Harvest

As the farmers prepared to harvest, they knew that the situation with the government was untenable and that they couldn’t continue to survive with wheat prices where they were. There were threats that they’d withhold their crops—but they didn’t know they’d be facing a much more unexpected foe that season.

Enter The Emus

Emus are flightless birds native to Australia, who may migrate hundreds of miles after their breeding season inland to find food and water on the coast. In the centuries before Western Australia was settled, their migration was unimpeded.

Carlos Delgado, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Carlos Delgado, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Mob Rules

As a result, they would sometimes gather in mobs—yes, a group of emu is known as a mob, not a flock—that could number in the thousands during the migration season. But then, settlement changed all that.

Petr Baum, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Petr Baum, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

It’s All About Balance

Before settlement, emus did face natural predators, including dingoes and thylacines—AKA, the Tasmanian wolf. And then there were Indigenous hunters. The emus lived on insects and plants, and the hunters on the emus. It was all in a balance. But when the farmers covered the land with wheat, it became a veritable buffet for the emus.

Newretreads, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Newretreads, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Good Fences Make Good Neighbors

At first, the farmers erected fences to protect their wheat from the emus, making their migration routes more complicated and circuitous. Until that is, the emus looked out for holes in the fences and some fell into disrepair over the years, leaving the wheat crops vulnerable to the emus.

Donald Hobern, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Donald Hobern, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

This Is Nice…

Increased food and water sources from the farmed land affected the migration routes of the emus. With less urgency to reach the coast, some emus would linger around the farmlands. And their timing couldn’t have been worse.

Haydyn Bromley, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Haydyn Bromley, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The 20K Mob

In 1932, various mobs of emu began to assemble together, eventually making up a group of over 20,000. They began to encroach on farms around the areas of Chandler and Walgoolan. Farmers, already dealing with unsatisfying wheat prices and missing subsidies, knew that this was a threat that could put them under—and they needed help right away.

South Australian Government, Picryl

South Australian Government, Picryl

Help!

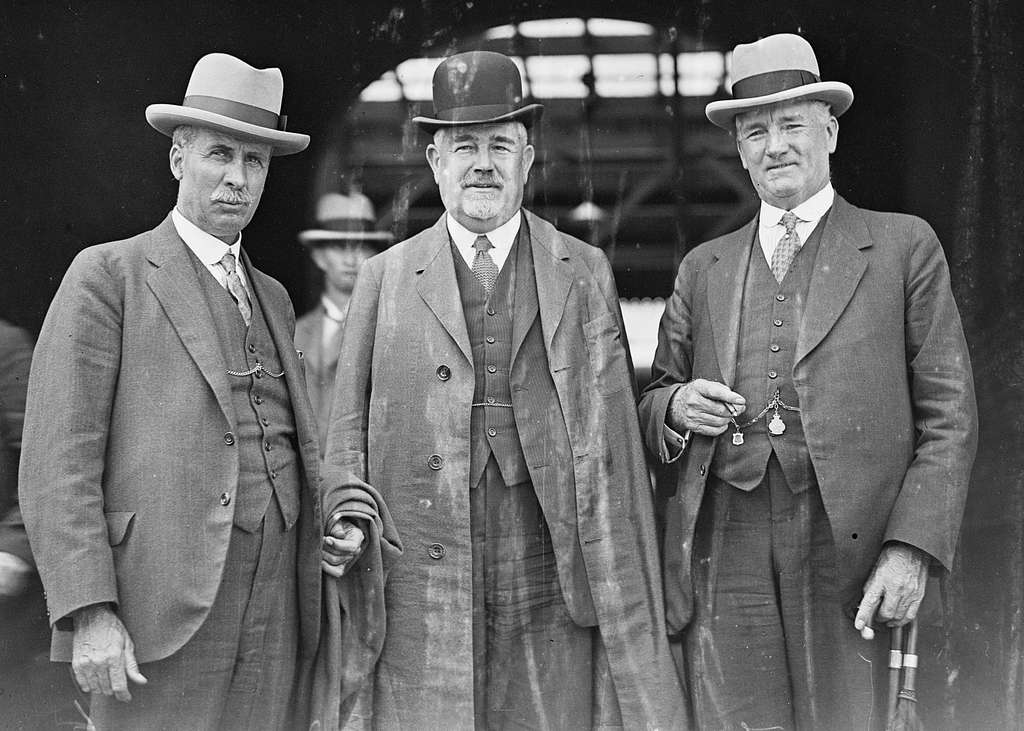

Veterans-turned-farmers reached out to the government for help, and eventually, a group of ex-soldiers met with the Australian Minister of Defence, Sir George Pearce. They had an idea for how to deal with the emus—and it was certainly drastic.

Swiss Studios, Wikimedia Commons

Swiss Studios, Wikimedia Commons

Talk About Overkill

Having fought in WWI, many of these veterans of service had become familiar with one of the newest tools of combat—machine guns. And when it came to their battle with the emu, they wanted to go big, so they asked the government for some heavy artillery.

UK Government artistic works, Picryl

UK Government artistic works, Picryl

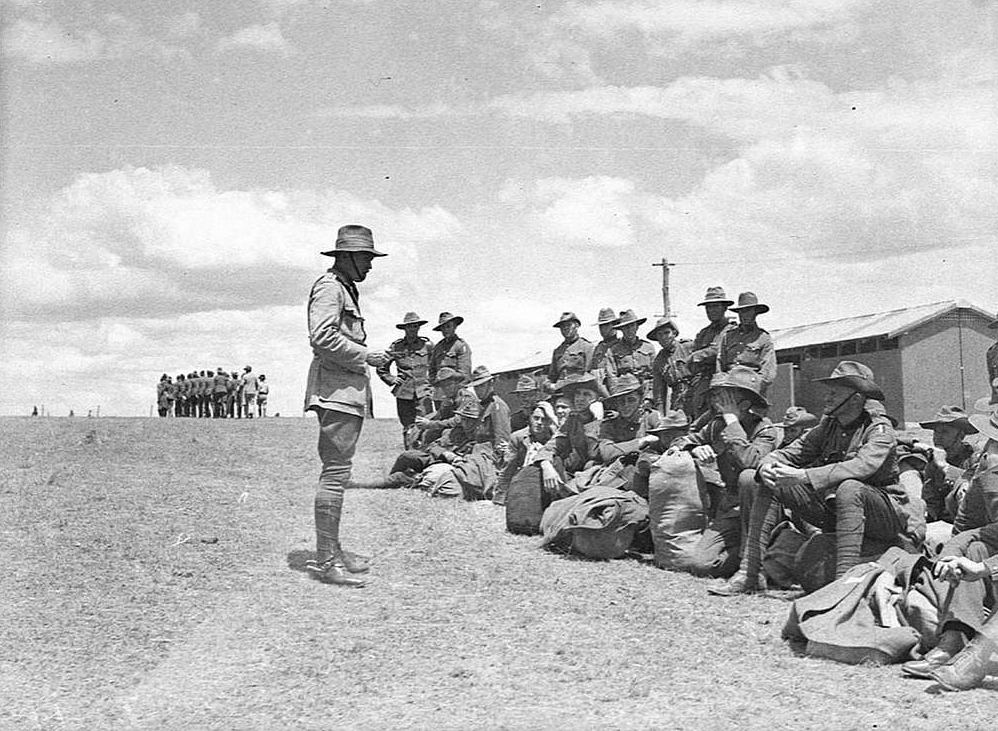

Let’s Make A Deal

The vets-turned-farmers struck a deal with the government. First, only trained personnel would have access to the machine guns. Second, the government would pay for troop transport, and the farmers would house and feed them, and pay for the ammo. It was a strange thing for the military to intervene in—but there may have been more to that story.

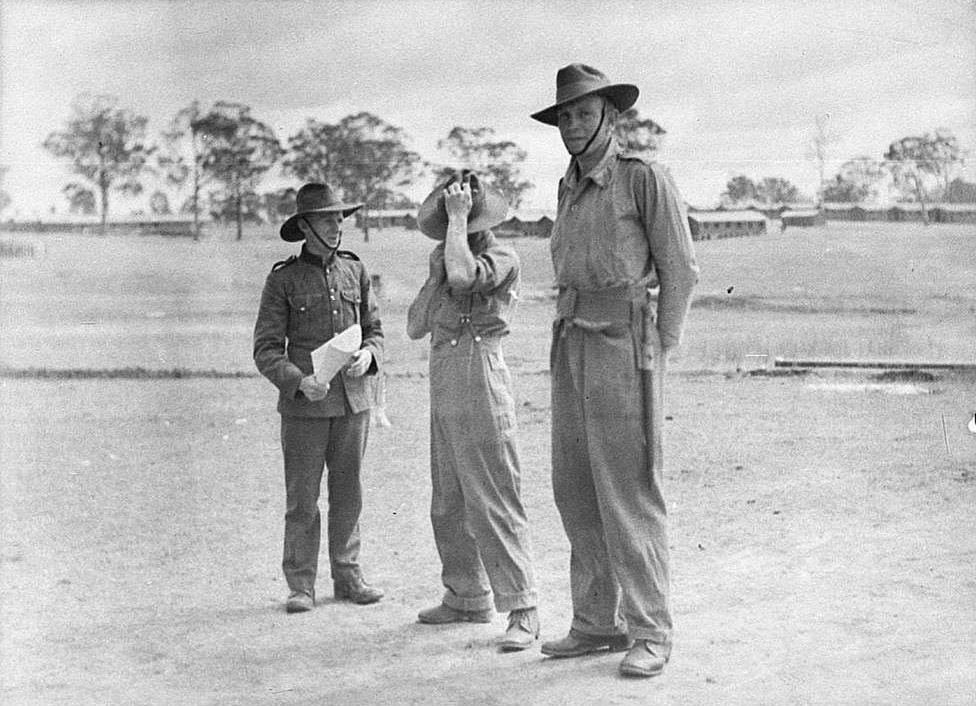

Australian War Memorial, Picryl

Australian War Memorial, Picryl

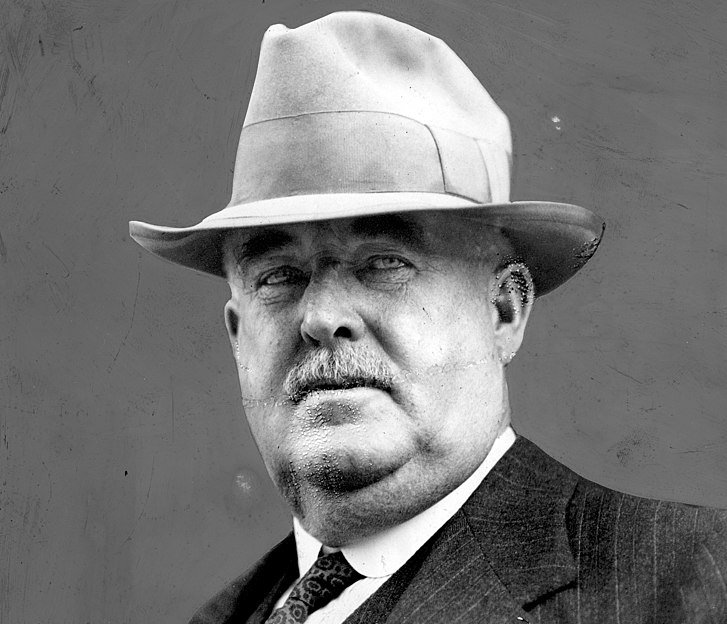

Pearce’s Ploy

The Minister of Defence, Sir George Pearce, claimed that sending troops to deal with the emus would make for good target practice—but he may have had other motives. There was a movement in Western Australia that aimed to secede.

South Australian Government, Picryl

South Australian Government, Picryl

United Against The Enemy

By helping out the farmers, who were extremely dissatisfied with the government, Pearce hoped to placate them and quash any effort toward secession. And thus, the Emu War was on.

National Library of Australia, Getarchive

National Library of Australia, Getarchive

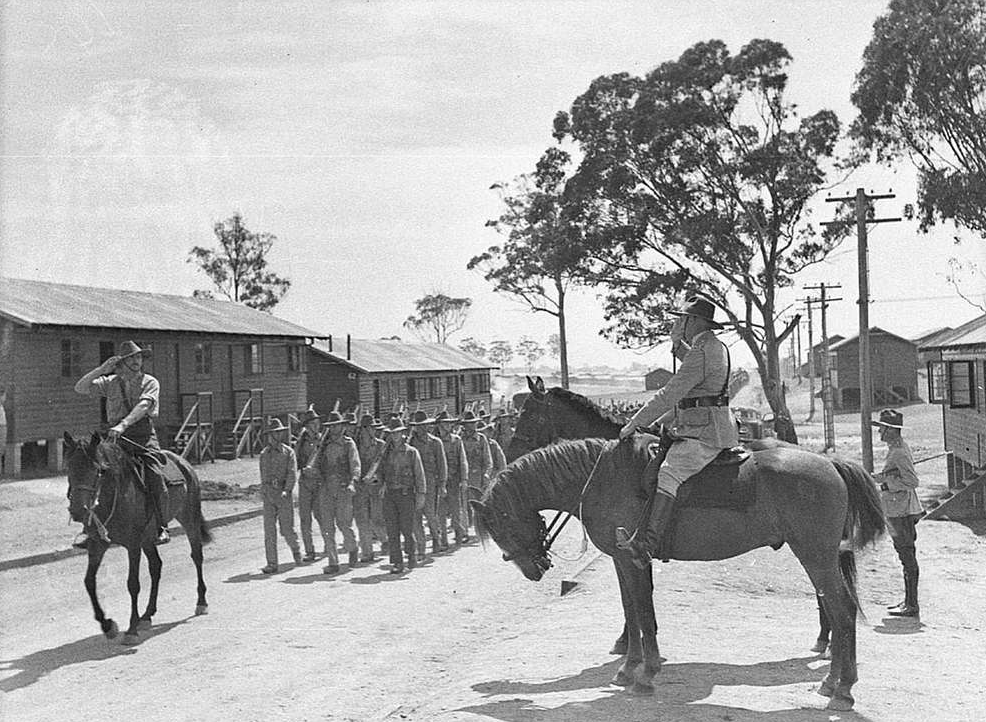

The Waiting Game

Major Gwynydd Purves Wynne-Aubrey Meredith of the Royal Australian Artillery's 7th Heavy Artillery commanded the small unit who deployed to the area to take on the emu. Heavy rains scattered the birds and the humans had to bide their time for the animals to return. Finally, on November 2, 1932, they got their chance to attack.

This Is War

Major Meredith, along with Sergeant McMurray and Gunner O'Halloran, opened fire on a mob of emus—but it quickly became clear they were in way over their heads. They expected to herd the birds toward the guns, and then simply fire and be able to take out hundreds of emus at once. That’s not exactly how it happened.

The Body Count

On that first day, the men were too far from the birds, affecting the range, and the emus scattered after being fired on. After two rounds of fire, the troops only took out a handful of emus that day. They knew that they had to take another approach.

If At First You Don’t Succeed…

Two days later, on November 4, the troops spotted a mob of about 1,000 birds and positioned themselves within firing range, hoping for more success in the war against emu. When they opened fire, they took out about a dozen emus...before the gun jammed. The rest of the mob fled.

A Worthy Opponent

The Australian military had sent three of their best to take on flightless birds known for their docility. Armed with machine guns, they’d only managed to kill a little more than two dozen birds. As the days went on and they failed to take out a significant number of emus, they began to notice something strange.

State Library of New South Wales, Picryl

State Library of New South Wales, Picryl

An Organized Effort

One of the troops noted that the larger mob had broken off into smaller groups, each of which seemed to be led by one of the larger birds, who would observe any danger and warn the others when people approached.

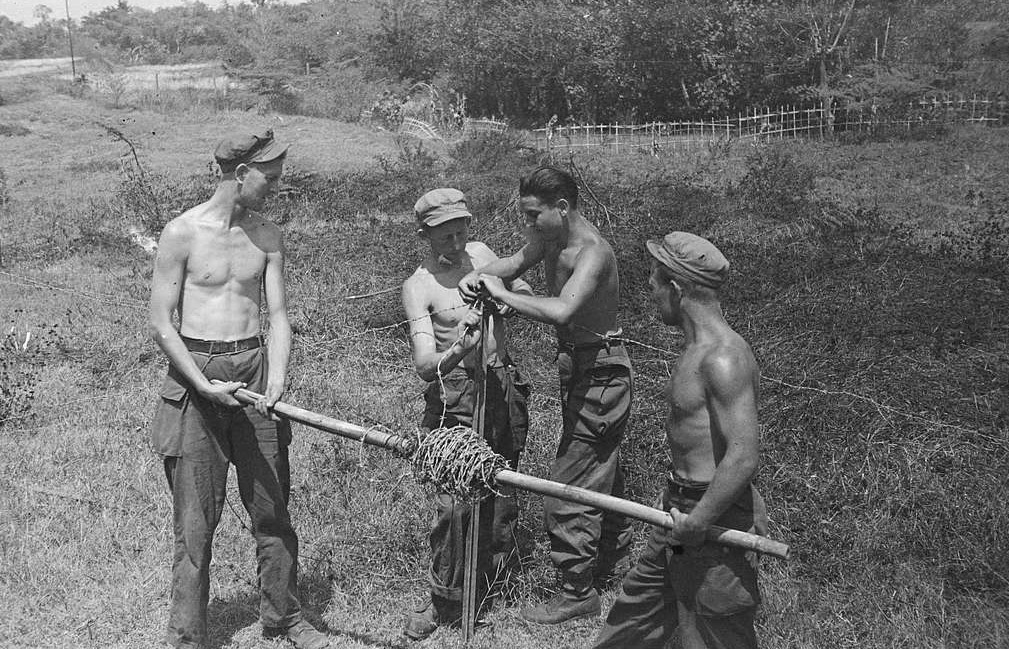

A Change In Strategy

Next, Major Meredith mounted the machine guns on trucks in hopes they’d be able to ambush the birds, but found that the terrain was too rough to properly operate them. Things were starting to get embarrassing.

The First Attempt By The Numbers

In six days of “battle” against the emus, Major Meredith and his men had fired over 2,500 rounds and had only managed to kill some 50 birds, though others reported that the number might have been closer to 200 or 500. Still, it wasn’t exactly the rout against nature that they’d expected.

Bad PR

As news of the failure to quell the emu population spread, the government was forced to address the humiliating spectacle. They decided to withdraw. Testimony from Meredith spoke to the impression the emus had made, and he even compared their speed and agility to the Zulu people.

Back Into Battle

The military had withdrawn, but the emus were still ravaging wheat farms all over Western Australia. The farmers asked the government to intervene again on their behalf. Their premier, James Mitchell, backed them up. The final reports for the initial attempt stated that they’d taken out some 300 emus. It was time to go back into battle.

State Library of Victoria, Wikimedia Commons

State Library of Victoria, Wikimedia Commons

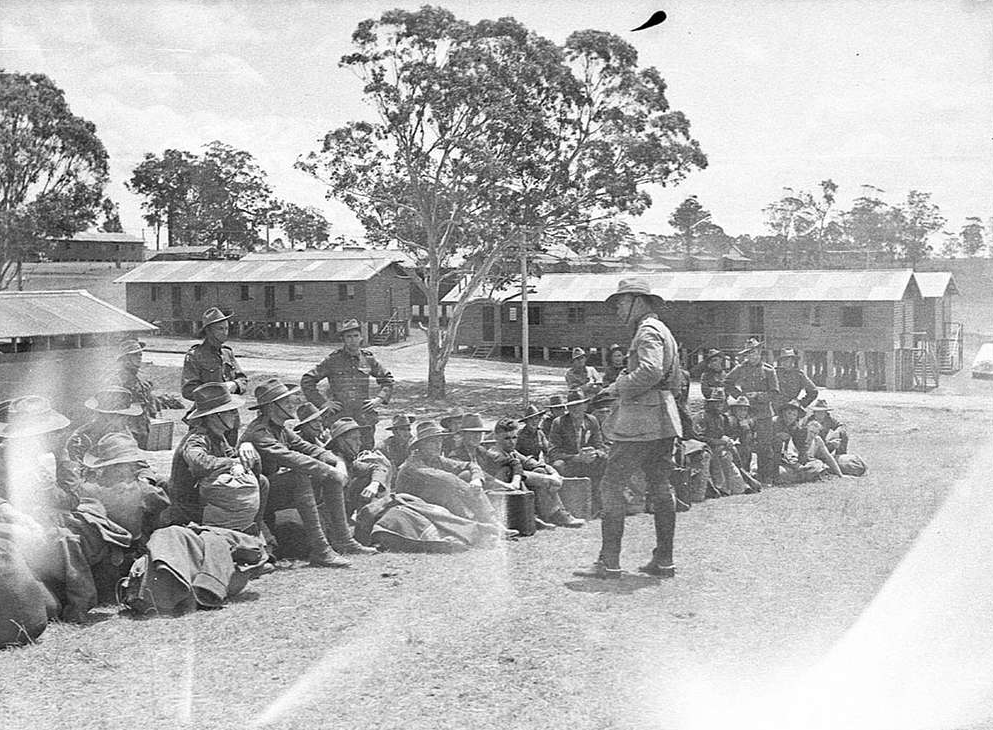

An Unpopular Conflict

A few days later, the Minister of Defence finally authorized another military effort to take on the emu population—though not without opposition. Major Meredith was set to lead again, as there was a serious shortage of men who were qualified to use the unit’s machine guns.

State Library of New South Wales, Picryl

State Library of New South Wales, Picryl

Take Two

The Australian troops went back into battle against the emus again on November 13, 1932. This time, they took out some 40 birds in the first few days of battle—but they ran into some bad luck on November 15, and their success rate went down.

The Unbeatable Enemy

Over the next two weeks, the men worked tirelessly to bring down the emu population, but they weren’t exactly massacring them. They were steadily taking out about 100 a week—but it just wasn’t enough. On December 10, the government recalled Major Meredith.

Jack Mallett, Wikimedia Commons

Jack Mallett, Wikimedia Commons

The Second Attempt By The Numbers

Reporting back, Meredith claimed that he and his men had taken out 986 emus, using 9,860 rounds of ammo—meaning that it took 10 rounds per bird. The odds weren’t great, though Meredith also reported that 2,500 birds had died from their injuries.

State Library of New South Wales, Picryl

State Library of New South Wales, Picryl

A Devastating Loss

The battle was over—and the Australian Army had lost against the mob of emus. It was an issue of contention in Parliament, as those in favor struggled to explain why they’d thought it was a good idea.

State Library of New South Wales, Picryl

State Library of New South Wales, Picryl

Falling On Deaf Ears

Of course, the defeat meant that the farmers were still left with emus to deal with. They asked for help from the government again in 1934, 1943, and 1948—but parliament wasn’t interested in repeating its mistakes, and left the farmers to deal with it on their own.

Royal Australian Historical Society, Picryl

Royal Australian Historical Society, Picryl

Bounty Hunters

Without the army, the government returned to the previous system they’d used for quelling the emu population, offering a bounty for the birds. And it turned out to be much more effective. In 1934, 57,034 bounties were claimed in six months.

State Library of New South Wales, Picryl

State Library of New South Wales, Picryl

The Wrong Side Of History

As the story of the failed war against the emus made its way across the world, the government of Australia faced even more humiliation—this time, along with criticism by conservationists who thought that they’d tried to perform a mass extermination against a native species.

National Library of Australia, Picryl

National Library of Australia, Picryl

The Battle Continues

After bounties, the next line of defense against the emu used by the wheat farmers of Western Australia was exclusion barrier fencing. In 1950, facing threat to their crops again, local legislators asked the government for more ammo, and received 500,000 rounds.

The Emu Problem Now

Western Australia continues to rely on exclusion barrier fencing to prevent pests from overrunning pastoral areas. Between 1901 and 1907, they erected the State Barrier Fence of Western Australia, which has also been nicknamed the rabbit-proof fence and the emu fence.

Fotocollectie Dienst voor Legercontacten Indonesie, Picryl

Fotocollectie Dienst voor Legercontacten Indonesie, Picryl

The Emu Fence

The State Barrier Fence consists of three sections and stretches thousands of kilometers—but from the beginning, it wasn’t particularly effective at keeping rabbits out of pastures. Today, the Australian government touts its effectiveness at preventing dingo and emu populations from encroaching on farmland.

Expanding The Fence

In 2013, plans to extend the State Barrier Fence were announced, but conservationists raised concerns that restricting the emus' accessibility to their migration routes might result in a mass extinction event.

Calistemon, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Calistemon, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Unbeatable Emu

Looking back on his failed battle against the emu, Major Meredith reported that: “If we had a military division with the bullet-carrying capacity of these birds it would face any army in the world [...] They can face machine guns with the invulnerability of tanks”.

It’s easy to laugh at the failure of a well-armed battalion against a flock of flightless, gentle birds—yet the numbers speak for themselves. At least it makes for a good story…

Coming To A Theater Near You

The story of the Emu War made its way to the stage in 2019 as a musical in Melbourne. Following its success, plans for not one, but two competing films about the events were announced. One made its way to the screens in 2023, while the other, starring John Cleese, Rob Schneider, and Jim Jeffries, is supposed to start filming in 2024.

Umbrella Entertainment, The Emu War (2023)

Umbrella Entertainment, The Emu War (2023)