In 1819, an elderly, deaf Francisco Goya purchased a house in the outskirts of Madrid. Even before he bought it, it was known as La Quinta del Sordo, or the House of the Deaf—but I’m sure he found the name fitting. He would give the house to his grandson five years later, and for decades, it sat in the Spanish countryside, attracting little attention. But Goya, one of the greatest painters in Spain’s history, had left something in that house. Nearly every wall was covered with scenes of sheer horror—the most disturbing and compelling work of Goya’s entire career.

The Black Paintings, which Goya painted directly onto the walls la Quinta del Sordo during his self-imposed exile from the Spanish Court, are unlike anything else he created in his long career. A man who became famous for light-hearted tapestry cartoons and portraits of European nobility spent some of his final days living alone in the country, painting dark, foreboding scenes of torment and anguish for no one in particular. The Black Paintings, it would seem, are the final cry of this genius mind—a mind that had been haunted by the ravages of sickness and war.

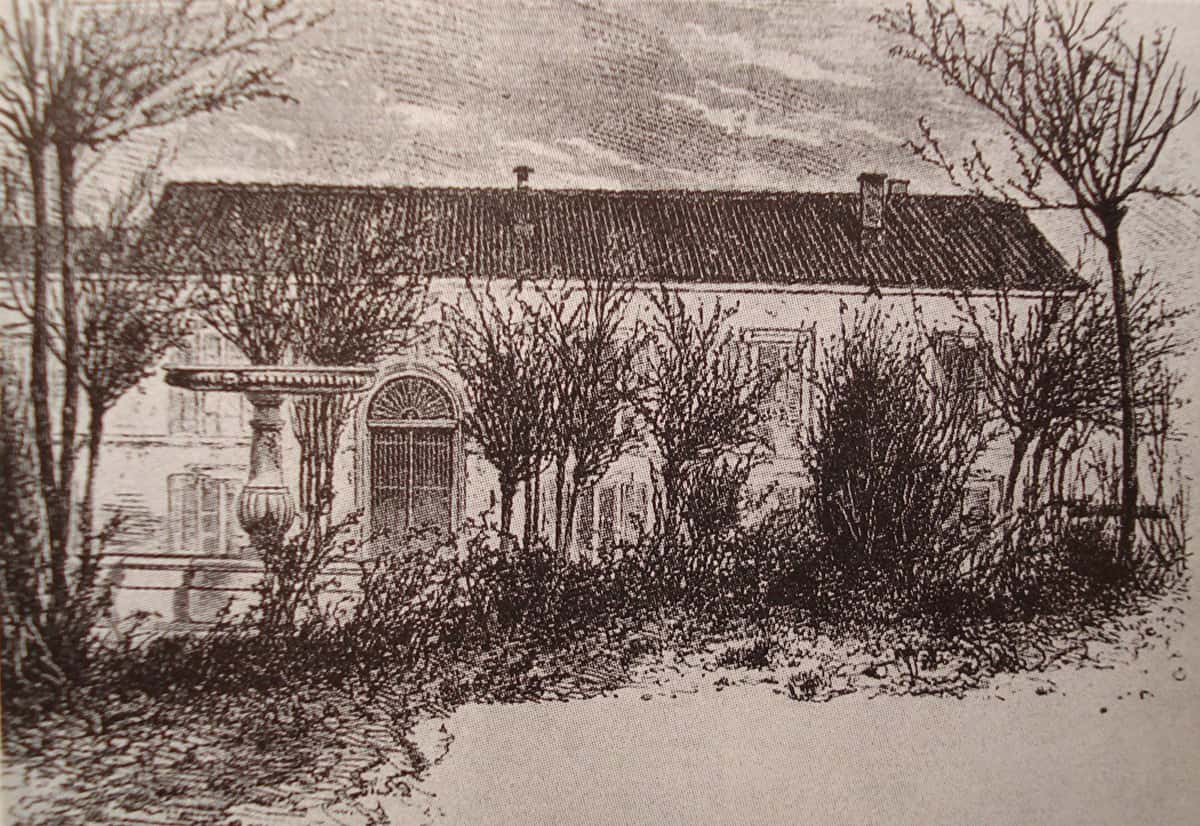

Wikimedia Commons Engraving depicting La Quinta del Sordo, where Goya created his black paintings.

Wikimedia Commons Engraving depicting La Quinta del Sordo, where Goya created his black paintings.

Francisco Goya started painting in 1760, when he was 14 years old. At the outset of his career, he spent four years painstakingly copying stamps until he felt ready to, in his words, “paint from my invention.” He initially worked in the Spanish city of Zaragoza, and while he eventually relocated to the more cosmopolitan Madrid, he struggled to gain a foothold in the art world. He applied to the Royal Academy of Fine Art of San Fernando twice, in 1763 and 1766, but was rejected each time.

After a trip to Rome to help hone his craft, Goya returned to Zaragoza, where he eventually started to see some success. He landed a commission to design a series of tapestry cartoons for the Royal Tapestry Factory in Madrid. Now, tapestries were not exactly considered prestigious, and Goya wasn’t particularly well paid for his work, but his popularist cartoons quickly became a hit. He got his name out there, and within a few years he was working as a portraitist for the Spanish aristocracy. He was finally elected to the Royal Academy in 1780; he became the painter to the king in 1786, then the official court painter in 1789. It took some time, but Goya had arrived.

The meteoric social climbing of Goya’s early career was nothing short of remarkable—from art-school reject to rubbing elbows with Europe’s elite. So, how did he go from the darling of the Spanish art world to a mad hermit, painting nightmares on the walls of his fortress of solitude? It would all begin in 1792, when a devastating illness would change Goya forever, and set him on the dark path to la Quinta del Sordo.

Wikimedia Commons Detail from Francisco Goya's "The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters."

Wikimedia Commons Detail from Francisco Goya's "The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters."

Though Goya’s illness was never identified, it nearly killed him, and it left him completely deaf. Fragile and isolated, Goya’s work began to grow dark and pessimistic—a stark contrast to the bright scenes that had brought him fame. Works such as his haunting painting Yard With Lunatics and the etching The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters reflect his souring world view. But as he continued to grow older, he would experience humanity’s ugly side first-hand, and his outlook would only become more and more bleak.

When the Peninsular War between France and Spain broke out, Goya had a front row seat to the brutal violence, and had an enormous effect on him. He refused to comment publicly on the conflict, but his work speaks for itself. His Disasters of War print series, along with his paintings The Second of May 1808 and The Third of May 1808, are melancholic and haunting, depicting atrocities on every side of the war. The lighthearted and snarky Goya of his early career was gone, replaced with a much more world-weary artist.

Pixabay Francisco Goya, "The Third of May 1808."

Pixabay Francisco Goya, "The Third of May 1808."

In the aftermath of the Peninsular War, King Ferdinand VII returned to power in Spain, and Goya—whose relationship with the king was strained at best—felt it best to withdraw from city life. He purchased La Quinta del Sordo in the country and secluded himself there. By this time, he had survived not just one, but two illnesses that nearly killed him. He had seen the horrors of war, and had watched his wife Josefa die. He was also 72 years old, completely deaf, and growing increasingly feeble. All of these factors are believed to have inspired the Black Paintings, Goya’s most enduring work.

Goya spent years painting lucrative commissions for Spain’s social elite, but in the House of the Deaf, he painted only for himself. By all accounts, his Black Paintings were never meant to be shown to anyone. They weren’t commissioned or sold. He painted them directly onto the walls, as if his isolated home were a physical representation of his tormented mind. He never mentioned them to anyone, and next to nobody would see them until years after he was dead.

The Black Paintings are almost entirely devoid of color, very rarely venturing beyond harsh blacks and browns. If Goya titled any of them, their names are lost—the titles they’re known by now were all invented by art historians years after the fact. They are undeniably his bleakest work, offering clear insight into the artist’s fraying mind. They have been exhaustively studied for nearly two centuries, but historians have failed to discover any cohesive narrative to the paintings outside their pervasive, incomparable pessimism.

There are 14 (potentially 15) of these paintings. They include Duel with Cudgels, which depicts two men beating at one another while they are each stuck knee deep in inescapable mud, and The Witches’ Sabbath, filled with tormented figures as the Devil, in the form of a giant he-goat, looms over them. But the most iconic of the Black Paintings is undeniably Saturn Devouring His Son, interpreted as a depiction of the Ancient Greek and Roman myth in which the titan Kronos (Saturn) eats all of his children alive.

Wikimedia Commons Detail of Francisco Goya's "Saturn Devouring His Son"

Wikimedia Commons Detail of Francisco Goya's "Saturn Devouring His Son"

After hearing that one of his offspring will overthrow him, Kronos (Saturn) decides that he will devour every child as soon as it is born. He eats infant after infant, but he can not avoid his fate. His wife tricks him and saves their final child, Zeus (Jupiter), who would see that the prophecy comes true. The myth has been portrayed in countless works of art, but none quite like Goya’s.

The haunting white of the headless corpse and the stark red of its blood stand out against giant’s muddy tones—but perhaps the most shocking aspect of the painting is the sheer horror on the giant’s face as it tears its child apart. The Kronos of myth eats each child with little remorse, but Goya’s Saturn is chillingly aware of how horrific the act is. He goes through with it anyway, desperate to cling to his power. The painting is a nightmare given form, and it seems a fitting culmination of Goya’s path from aspiring artist to court darling to haunted wreck.

The Black Paintings sat hidden in La Quinta del Sordo for decades. Eventually, a French banker named Baron Émile d’Erlanger paid to have them removed from the walls of the house and transferred onto canvas—a process that was done haphazardly at best. In one writer’s words, they were "hacked off the walls and attached to canvas.” They suffered serious damage in the transferal process, and needed heavy restoration, meaning that the paintings that today hang in the Museo del Prado in Madrid are considered to be a “crude facsimile” of Goya’s original work.

For his part, Goya likely wouldn’t care. Not all great art is made to be hung in a palace or a museum. This Spanish master artist created the Black Paintings for himself alone—his exhausted and weary mind thrown onto the walls of his house, if just to get some respite from the demons that plagued him.